What Will Push the Last Single-Academy Trusts to Merge?

This article originally appeared in Tes Magazine. Sign up to our free newsletters by registering for free at https://bit.ly/43w8ntN and ticking ‘Daily’ in your profile

England is now losing roughly one single-academy trust every five days, and the number of SATs has fallen by almost a third in just five years, Tes analysis shows.

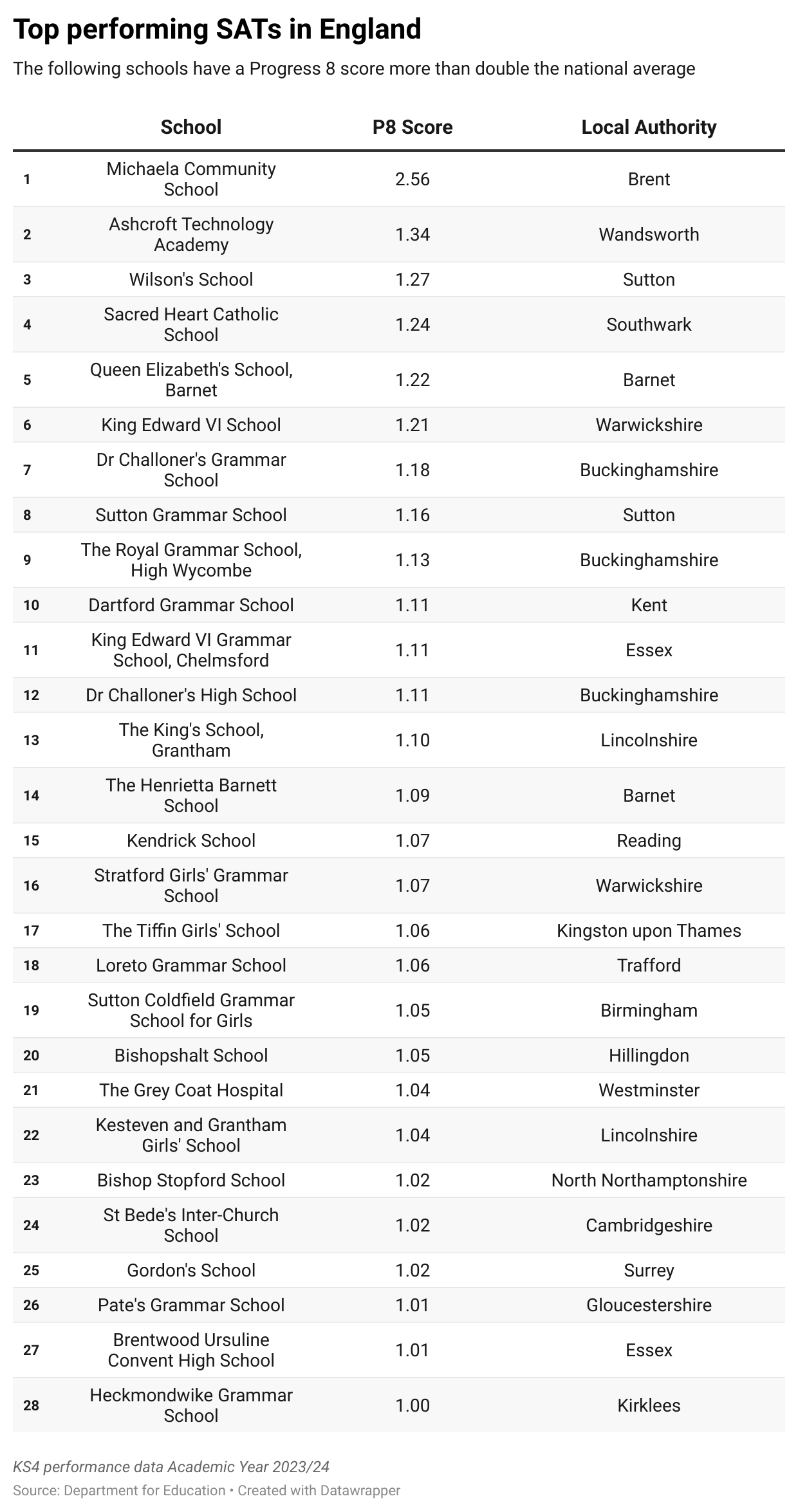

Despite this, nearly 850 SATs remain and some of them have among the highest Progress 8 scores in the country.

The Labour government’s upcoming Schools White Paper is widely expected to encourage all schools to join a multi-academy trust, or at least a “family of schools”. The final language that the DfE will use in this policy document is unknown, but the direction of travel points towards fewer standalone schools.

If this policy is confirmed, it would mean all schools move beyond voluntary collaboration to an expectation that none operates alone.

The question for ministers is whether schools that are high-performing and financially stable will see any reason to give up their autonomy, or if Labour will have to go beyond persuasion to make such a policy work.

So, how many SATs will choose to stay put, against a backdrop of financial pressure, and what will it take to convince high-performing schools to give up their autonomy?

The decline of single-academy trusts

There has been an increasing trend of maintained schools and single-academy trusts merging into MATs in recent years, both voluntarily and forced.

While there are 1,200 MATs in England, the total number of SATs fell from 1,252 to 848 between September 2020 and September 2025 - a loss of 404 schools (32.3 per cent), Tes analysis of Department for Education data shows.

Only four new SATs have opened in the past five years, and none since 2024.

Some 70 schools left SAT status in 2020-21, compared with 74 the following year, 82 in 2022-23 and a record 106 in 2023-24 - an annual fall of more than 10 per cent. The latest 2024-25 data shows a further decline of 72 schools (7.8 percent).

.png?width=1240&height=1300&name=j1U2Y-year-on-year-decline-in-sats%20(1).png)

Some of this reduction is down to deliberate policy decisions: the previous Conservative government promoted larger trusts as the most sustainable way to share leadership, staff and resources.

Labour’s plans appear set to continue that trajectory, though the exact policy levers it will use remain unclear. But sector experts also say that the SAT model is increasingly becoming financially and administratively unsustainable.

Some evidence for this viewpoint is provided in the Kreston-Bishop Fleming Academies Benchmark Report 2025, which identifies SATs as “the most financially vulnerable part of the sector”.

Two-thirds (66.7 per cent) of secondary SATs in the report ran in-year deficits in 2023-24, while primary SATs have recorded losses for three years running.

Trustees told auditors that there is now “little fat left to trim”, and any further unfunded staff pay awards or national insurance rises risk pushing them deeper into deficit.

Larger MATs, by contrast, tended to break even, holding reserves of 8-10 per cent and benefiting from shared staffing and procurement savings that single schools cannot match.

There is also growing political pressure on smaller trusts, for example over executive pay. In November 2023 the Education and Skills Funding Agency wrote to 37 academy trusts questioning the amount their CEOs had been paid. Some 14 of the trusts flagged as outliers were SATs, adding pressure on to leaders.

What will make SATs join MATs?

The government has two challenges: persuading struggling SATs that joining a MAT is a lifeline and convincing thriving ones that collaboration will not dilute their success.

With Labour expected to use its White Paper to support more formalised school collaboration, sector figures say ministers already have powerful levers to encourage smaller trusts to merge into larger ones.

Mark Blackman, director of education consultancy Leadership Together, says there is a range of measures the DfE could use to incentivise SATs to join a larger trust.

Only MATs have access to the School Capital Allowance (SCA) grant, he says, and smaller trusts must rely on the Condition Improvement Fund (CIF), which is difficult to secure. There is, therefore, a clear incentive to join a larger organisation where funding is apportioned per pupil.

Blackman adds, however, that the costs of structural change, including legal and contractual fees, could still deter mergers, especially for smaller schools.

Manny Botwe, headteacher of Tytherington School, a SAT in Cheshire, says his school is also reflecting on what the White Paper might mean for single-school trusts. The school regularly reviews whether it should join a trust, he says.

There is now “very little ideological opposition” to joining MATs, Botwe tells Tes. But schools want assurance that the “top-slice represents value for money”, he says, referring to the practice of MATs taking a proportion of each school’s funding to create a central fund. And they also want to know that support for school improvement is strong.

“For us, a big thing is being part of a group of schools that is locally meaningful,” Botwe says.

He adds that financial pressure is a major factor shaping decisions; however, “joining a MAT doesn’t necessarily solve that problem”.

For some larger SATs, however, the picture looks different. Gwyn Williams, headteacher of Lymm High School in Warrington - a school with 1,924 pupils and a Progress 8 score of 0.71 - says his school has “never been opposed to MATs” but has yet to see the “significant, concrete benefits” from joining one. “It’s hard to see what the government could say or do to change this,” he adds.

Williams says Lymm High can already collaborate “on our own terms” and worries that joining a MAT would mean “giving up independence for little gain”.

The push, then, comes from financial difficulties. For many SATs, budgets are shrinking, and the economies of scale available in large trusts are increasingly hard to ignore.

The pull, however, lies in the promise of shared support, stability and resources. Whether that balance will be enough to convince all SATs to join larger trusts remains to be seen.

But for high-performing SATs, the question may be less about survival and more about finding a trust that shares their ethos.

What kind of SATs are disappearing?

Tes analysis of DfE data shows that the decline in SATs is concentrated among mainstream schools.

Between 2020 and 2025, the number of secondary SATs fell from 624 to 434 (by 30 per cent) and primary SATs from 506 to 328 (by 35 per cent). All-through and special-school SATs have also reduced, but at a slower rate, while 16-plus colleges have remained stable.

Regional shifts

Yorkshire and the Humber has lost more than half of its SATs - down 53 per cent, from 96 to 45. The South West is down 38 per cent (70 schools), and the West Midlands has dropped 36 per cent (52). The East Midlands and North West have both fallen by around 35 per cent.

.png?width=1240&height=1300&name=ZFlef-how-many-sats-have-closed-down-in-each-region-%20(1).png)

London, with a smaller proportional fall (23 per cent), still has the largest number of SATs overall (140).

At the local authority level, Hertfordshire (43), Kent (35) and Lincolnshire (34) host the biggest remaining clusters. By contrast, northern and Midlands regions have seen more aggressive MAT growth.

According to Blackman, this regional pattern aligns with where the DfE has “pushed hardest” for collaboration, particularly in areas with weaker economies of scale or historical underperformance.

Academic performance

Despite financial and political pressure to merge, why is it that some SATs seem to be not only surviving but also thriving, delivering some of the best Progress 8 scores in the country?

When specialist university technical colleges (UTCs) and studio schools are removed from the data, the performance of single-academy trust secondaries looks strong.

Across 422 secondary SATs, the mean Progress 8 score is 0.26 - meaning pupils make above-average progress compared with peers nationally. The median sits almost identically at 0.25, suggesting a consistently positive trend rather than one skewed by a few outliers.

.png?width=1240&height=514&name=hAYIY-sats-the-range-of-progress-8-scores-by-region%20(1).png)

The strong academic records raise a key question for the government’s expected White Paper: if Labour’s goal is for every school to be part of a MAT, what incentive would convince academically successful, financially stable SATs to give up their autonomy?

In total, 69 per cent of SATs record Progress 8 scores above zero, while only 30 per cent fall below the national baseline. Just 1 per cent sit exactly in line with it.

The weakest SATs tend to be small or coastal secondaries, echoing national patterns of lower performance in isolated areas.

The high performers

At the other end of the scale are those with academic results and reputations that have helped them to weather financial storms. Around 18 per cent of SATs (85 schools) are selective, Tes analysis shows, compared with 5 per cent of all state schools in England.

Among the top performers is Dartford Grammar School, which became an academy in 2011 and remains a single-academy trust. The school recorded a Progress 8 score of 1.11 in 2024 - the tenth highest among all SATs in England.

Headteacher Julian Metcalf says the model has “served the school well”, allowing it to have an International Baccalaureate curriculum that is “aligned to our values and our students”.

He says the school already collaborates with groups and is “open-minded” about joining a MAT in the future, provided it has “the right circumstances and ethos”. “There are clear financial and operational drivers to joining a MAT,” he says.

“Every school is a unique community, but much comes from the ability to collaborate with peers and other professionals - sharing experience and resources are some of the best drivers of school improvement.

Williams, from Lymm High, says his concern is “almost the opposite” of smaller schools that need additional support. “We probably have the capacity to support other schools more than we already do,” he says, but routes for doing so have become “less obvious” as support is funnelled through trusts.

Over time, he warns, that could “limit professional development and waste capacity that could be helping the wider system”.

Botwe echoes this view, saying that both formal MATs and looser local school networks could succeed if collaboration was genuine.

It is also important to note that financial challenges are not unique to SATs: an analysis shared exclusively with Tes last month revealed that more than half of MATs were forecasting an in-year deficit this academic year.

If the government’s aim is for every school to join a MAT, convincing schools such as Dartford Grammar and Lymm High, which appear to be excelling on their own, may prove to be a tough challenge.

Would MATs even want them?

But not all large trusts are eager to take on standalone schools. Small transfers can bring limited benefit compared with merging with an entire MAT, given the due diligence and legal costs involved, according to Blackman. He says the DfE may need to underwrite or subsidise those costs to make future mergers viable.

Marc Doyle, CEO of Quest Trust, a MAT of four primary schools and one secondary based in Wigan, says, however, that from a multi-academy trust perspective, SATs can be “highly attractive partners”. “They often bring strong leadership, proven results and local connections, helping to extend the trust’s impact into new communities,” he says.

Doyle argues that the removal of DfE capacity funding has made mergers more challenging, and there should be new ways to incentivise collaboration.

Leora Cruddas, chief executive of the Confederation of School Trusts, says there is “room for lots of different types of trusts”, adding that some single-academy trusts “can continue to be high-performing both academically and operationally”. But she argues that “the clear benefits of being part of a family of schools” have driven the growth of collaboration across the sector.

What’s next?

The data on SATs paints a picture of academic resilience but financial fragility. If current trends continue, we could have fewer than 600 SATs by 2030.

Tom Richmond, an education policy analyst and former DfE adviser, says the figures show that “the direction of travel is still very much pointing towards families of schools working together and fewer schools left to fend for themselves”.

He warns that, with a new Ofsted inspection framework and curriculum changes ahead, “operating within a family of schools could prove even more useful”.

The question for the government, then, is whether the next phase of reform will rely on persuasion or compulsion, and whether the push and pull of funding, accountability and collaboration will be enough to bring even the highest performers on board.

So while the single-academy trust model still has its defenders, the gravitational pull of the MATs appears stronger than ever. For most schools, collaboration may no longer be a choice but a condition of survival.

.png)

%20in%20With%20the%20New%20(Assessment)%20Rethinking%20How%20We%20Assess%20Students%20-1.png)

-Sep-01-2023-08-26-26-1239-AM.png)